6. St. Josaphat’s Catholic Basilica, 1897

601 West Lincoln Avenue

Architects: Erhard Brielmaier and Sons

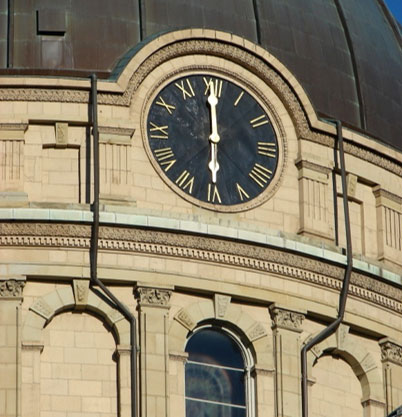

The Basilica of St. Josaphat is Milwaukee’s largest church, accommodating more than 2,000 worshippers at a time. St. Josaphat’s also has the city’s most magnificent interior space, with its richly ornamented walls, ceiling vaults, and colossal dome. Among pre-World War II buildings in Wisconsin, only the Yerkes Observatory in Williams Bay (1897) and the Capitol in Madison (1917) have larger domes.

St. Josaphat’s was clearly inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, a Renaissance/Baroque church constructed in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. It also bears some resemblance to the later St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, designed by Sir Christopher Wren and built from 1675 to 1720. In addition to being an architectural masterpiece, St. Josaphat’s is a monument to the city’s Polish-Americans and their Catholic faith.

The Archdiocese of Milwaukee established St. Josaphat’s Parish in 1888 to accommodate the city’s growing Polish immigrant population. Another Polish Catholic church, St. Vincent de Paul, was established on the South Side in that same year, following St. Hedwig’s on the Lower East Side (1871) and St. Hyacinth on the South Side (1882). All of these are daughters of St. Stanislaus, the city’s first Polish Catholic Church.

The first church building for St. Josaphat’s, erected in 1888, burned down less than a year after its completion. A new building put up the following year, housing both the church and school, stood to the immediate west of the present church. By 1896, the parish had grown to more than 12,000 members and desperately needed a larger church.

Milwaukee architects Erhard Brielmaier and Sons received the commission to design the new church for St. Josaphat’s. Erhard Brielmaier (1841-1917) was born in the Wurttemberg region of southwestern Germany, at that time a separate kingdom. His family immigrated to the United States in 1850, settling in Cincinnati. The young Brielmaier learned carpentry and construction from his father but also took an interest in building design from an early age. Moving to Milwaukee in the early 1870s, Brielmaier initially worked as a carpenter and woodcarver, specializing in altars and other church furnishings. His business was not confined to the Milwaukee area. Newspaper accounts from the late 1870s note that Brielmaier created altars for Catholic churches as far away as Minnesota and Indiana.

Three of Erhard’s sons, Bernard, Joseph, and Leo, joined their father’s business, which from about 1890 was known as E. Brielmaier and Sons. The firm’s transition from carpentry and altar building to architecture was gradual. Frank Flower’s History of Milwaukee, published in 1881, refers to Erhard Brielmaier as an “architect, sculptor, and builder” (p. 1501). City directories prior to 1896 listed the firm in the business section under the categories of “altar builders” or “church furniture manufacturers.” From 1896 on, the firm was listed under “architects.” The extent of the firm’s architectural work prior to the commission for St. Josaphat’s is not known, but appears to have been modest. There are few buildings in Milwaukee that predate the church and are known to have been designed by the Brielmaier firm.

The success of St. Josaphat’s opened the door to many more commissions for Catholic churches, which became the Brielmaier firm’s specialty. Although the firm continued to design altars and other furnishings for their church commissions, it is unlikely that they continued to build their own designs while running a large and growing architectural office. Erhard Brielmaier died in 1917, but his sons continued the firm under the same name into the 1950s. In addition to St. Josaphat’s, Erhard Brielmaier and Sons designed four other Catholic churches in Milwaukee and many more elsewhere in Wisconsin and across the country. By 1930, the Brielmaier firm had done work in 21 states, from Massachusetts to Arizona. The firm worked primarily for the Catholic Church over the course of six decades, designing school buildings, seminaries, convents, hospitals, and other types of buildings in addition to churches.

For St. Josaphat’s, the architects initially designed a church to be built of brick with terra cotta trimmings, similar in its overall form and style to the church as built. The estimated construction cost for this building was $150,000. Before construction got underway, Father Wilhelm Grutza of St. Josaphat’s, in charge of the building project, learned that the Post Office and Customs House in Chicago was about to be demolished. Father Grutza traveled to Chicago and purchased the salvage rights to the materials for $20,000, less than half the estimated cost just for the brick for the Brielmaier firm’s proposed design. Materials taken from the dismantled Chicago building included not only 200,000 tons of stone, but also wood doors, bronze railings, light fixtures, and even doorknobs and other hardware. The stone acquired in Chicago included some marble in addition to many tons of light brown Ohio sandstone, and also the six granite columns that are now part of the front portico of the church, each more than 30 feet in height.

Father Grutza had all of the material shipped to Milwaukee, which required 500 railroad cars. Every piece of stone and other material was then numbered, measured, catalogued, and placed in a storage yard near the construction site. The architects then had to redesign the building to accommodate the newly acquired materials. For reasons of economy, they sought to use only the Chicago material to the extent possible, while cutting or reshaping as few of the individual stones as possible. The process was rather like constructing a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, with the added complication that the pieces had to be assembled to form a new and architecturally cohesive building rather than a reconstruction of the original Chicago post office.

Construction of the church began in 1896, with the cornerstone laid in July of the following year. The men of the parish supplied much of the construction labor, including excavation for the basement and foundations. Dedication ceremonies for the new church were held in July of 1901.

At the time of the building’s completion, the dome was one of the largest in the United States, with a diameter of about 80 feet and a height of just over 200 feet from the sidewalk to the top of the gold cross that surmounts the dome. This is a greater height than all but a few of the city’s church steeples. The dome is framed in structural steel, material that did not come from the Chicago building. This was an early application of structural steel for the construction of a large dome, as most of the earlier domes in the United States are of cast iron.

Although the building was complete enough to be occupied in 1901, the interior was a bare white throughout. The elaborate interior decoration scheme seen today was not carried out until the late 1920s, after the initial construction debts had been paid and new funds became available. All of the interior painting was restored in the 1990s, along with structural retrofits to the building and a new roof, including new copper cladding on the dome.

Pope Pius XI designated St. Josaphat’s a basilica in 1929, shortly after completion of the interior decoration. The basilica designation is an honorary title accorded to Catholic churches of great age, historical significance, or outstanding architectural and artistic merit. St. Josaphat’s was only the third church in the United States to receive this honor.

Sources:

Borun, Thaddeus, ed. We, the Milwaukee Poles. 1946.

“Brevities,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 4, 1878, page 8, column 2.

“Brevities,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 4, 1879, page 8, column 3.

Brielmaier, Erhard and Sons, architects. Drawings for construction of St. Josaphat’s Church, some dated 1896. Wisconsin Architectural Archive, Milwaukee Central Library, drawing set 31-4.

Brielmaier, Erhard and Sons, architects. The Work of E. Brielmaier & Sons Co., Architects, Milwaukee: 1865-1930, c. 1930.

“Death Summons Church Architect” (obituary of Erhard Brielmaier), Milwaukee Sentinel, August 30, 1917, page 1, column 2.

Flower, Frank A. History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Western Historical Company, 1881. Facsimile reprint by the Milwaukee Genealogical Society, 1981.

Glastetter, Michael J., and Joseph Switanowski, eds. The Basilica of Saint Josaphat. Basilica of St. Josaphat, 2002.

Gurda, John. Centennial of Faith: the Basilica of Saint Josaphat, 1888-1988. Basilica of St. Josaphat, c. 1989.

__________. “The Church and the Neighborhood” in Milwaukee Catholicism, edited by Steven M. Avella. Knights of Columbus, 1991.

Kaluzny, Pius, and Samuel Bonikowski, eds. The Basilica of St. Josaphat, Bishop and Martyr. Conventual Press, 1952.

Souvenir Album of the Golden Jubilee of the Dedication of St. Josaphat’s Basilica, 1901-1951. St. Josaphat’s Basilica, 1951.