15. St. Paul’s Episcopal, 1883

914 East Knapp Street (at Marshall Street)

Architect: Edward Townsend Mix

St. Paul’s is the oldest Episcopal parish in Milwaukee, established in 1838. The congregation met at several different locations during its earliest years, before building its first church in 1844. The annual report of the parish from 1881 described that church as “past patching” and “now approaching a hopeless decrepitude,” leading to the decision to build a new church (Troeger, p. 15).

The parish conducted a limited competition for the design of the new church, inviting five architectural firms to submit designs. The entrants included three prominent East Coast firms: William G. Harrison of New York, Richard M. Upjohn of New York, and the partnership of Ware and Van Brunt of Boston. Two Milwaukee architects, Edward Townsend Mix and Howland Russell, were also invited to compete for the commission.

The winner of the competition, E.T. Mix (1831-1890), was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He began an apprenticeship in 1848 in the New Haven office of Sidney Mason Stone, a prominent New England architect and designer of many churches. Mix moved to Chicago in 1855 and formed a brief partnership with William Boyington. The firm of Boyington and Mix opened an office in Milwaukee in 1856, where Mix had relocated to supervise the construction of two of the firm’s projects. Severing the partnership the following year, Mix remained in Milwaukee and practiced here for more than thirty years, leaving for Minneapolis in 1888.

Mix was one of the city’s earliest professionally trained architects, rather than a carpenter or builder who later assumed the role of architect. By the time of the competition for St. Paul’s Church, he was the most distinguished architect in Milwaukee, having designed numerous mansions for the city’s wealthiest citizens and two churches just a few blocks from the St. Paul’s property in the Yankee Hill neighborhood: Olivet Congregational (now All Saints Episcopal Cathedral) of 1868 and Immanuel Presbyterian of 1873. Among his many commissions for commercial buildings were two of the city’s greatest expressions of Victorian exuberance, the Mitchell Building of 1876 and the Grain Exchange Building of 1879, which stand side by side on East Michigan Street downtown.

Mix won the competition for St. Paul’s Episcopal with a Richardsonian Romanesque design that differed in some respects from the church as built. The original design included circular windows in the transepts, while the shorter tower on the right side of the façade was to have a round upper stage with a conical roof. In developing the design details prior to construction, Mix changed the transept windows to tall, round-arch forms. He also redesigned the southeast tower, making all stages square in plan and eliminating the conical roof.

The design that Mix originally proposed bears a strong resemblance to a design by Charles Gambrill and Henry Hobson Richardson for a church in Buffalo, New York. Although the Gambrill and Richardson church was never built, a rendering of the design was published in The Architectural Sketch Book of October 1873. The rendering by Gambrill and Richardson and the competition entry by Mix both show a tall corner tower on the left side of the façade, a shorter tower with a conical roof on the right side, and circular windows in the transepts as well as on the façade. The resemblance between the two buildings is so strong that Mix must have seen the published rendering and borrowed from it for his own church design. This sort of direct imitation was common at the time and was not considered unethical. (Today, such borrowing from the work of other architects would likely invite a lawsuit.) The design by Mix shows the great influence that Richardson’s work had on architects throughout the 1880s and into the 1890s. It also illustrates the fact that architects working in the historical revival styles, particularly during the late nineteenth century, were generally not seeking inspiration from the original buildings of the Romanesque, Gothic, or other historical periods. Instead, they were looking at the recently published work of the leading figures among their contemporaries.

Construction of the church began in the fall of 1882 and continued for two years, with the first service in the completed building on October 12, 1884. The stone for the walls came from Basswood Island, one of the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior. There were several quarries along the shoreline and on some of the islands of Lake Superior at this time, in Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, all producing sandstone of reddish-brown color. This stone was not used extensively in Milwaukee, since there were limestone quarries nearby and brick factories in the city. The Milwaukee County Courthouse of 1872, demolished in the early 1930s, was probably the largest building in the city to be constructed of Lake Superior sandstone. St. Paul’s Episcopal is one of only a few surviving buildings in the city to use this material.

The tall tower on the building’s southwest corner is more than 120 feet in height. Due to a shortage of funds, this tower was initially completed only to approximately the same height as the southeast tower. The upper stages of the tower, including the carved angels, were completed in 1889. The angels are another feature inspired by one of Richardson’s buildings, in this case the Brattle Square Church of 1872 in Boston. The competition rendering by Mix shows the angels blowing their trumpets, as at the Brattle Square Church. In the sculptures as executed, the angels are holding their trumpets at their sides. This change was perhaps made by the architect or the sculptor to avoid copying Richardson’s work too literally.

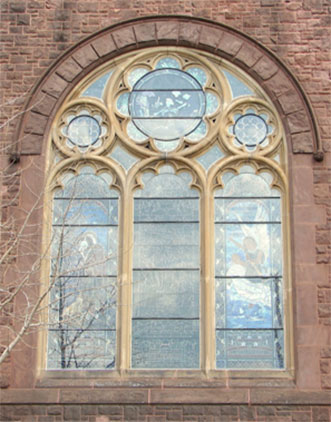

St. Paul’s has an impressive collection of stained glass windows by several different manufacturers, dating from the 1880s to 1944. The oldest windows, installed in 1884 as part of the original construction of the church, are mostly by McCully and Miles of Chicago. There are also two Tiffany windows dating to 1884 and nine other Tiffany windows dating from the later 1880s to at least 1915. The east transept window is believed to be the largest window ever produced by Tiffany’s firm, measuring 22 feet wide by 32 feet high.

Sources:

“City Brevities,” (reference to completion of the west tower of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church), Milwaukee Sentinel, September 20, 1889, page 3, column 3.

Eckert, Kathryn Bishop. The Sandstone Architecture of the Lake Superior Region. Wayne State University Press, 2000.

Flower, Frank A. History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Western Historical Company, 1881. Facsimile reprint by the Milwaukee Genealogical Society, 1981.

“Founded Upon a Rock,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 7, 1882, page 2, column 3.

Gambrill and Richardson, architects. Drawing for unexecuted Trinity Church in Buffalo, New York. Architectural Sketch Book, October 1873.

Guth, Alexander C. “Early Day Architects in Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, September 26, pages 17-28.

Mix, Edward Townsend, architect. Drawings for St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, undated. Wisconsin Architectural Archive, Milwaukee Central Library, drawing set 4-10.

“The New St. Paul’s,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 17, 1882, page 2, column 3.

“The New St. Paul’s,” Milwaukee Sentinel, Sept. 28, 1884, page 6, column 4.

“St. Paul’s Church,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 19, 1882, page 6, column 4.

Szczesny-Adams, Christy. Cosmopolitan Design in the Upper Midwest: the Nineteenth Century Architecture of Edward Townsend Mix. Ph. D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 2007.

“A Tower to Go Up,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 8, 1889, page 3, column 5.

Troeger, Agnes Boyd. History of Saint Paul’s. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, 1984.